Duncan at war 1914

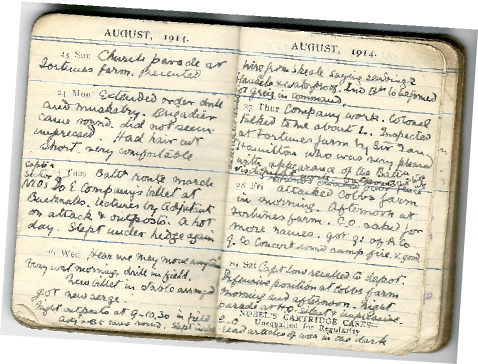

Duncan kept a diary for much of his adult life. When he left for France in 1914 he took with him a small shooting diary. The entries are often in note form, usually written in pencil. Some comprise just one word, presumably to remind him of a particular event. He also wrote to his family and friends almost daily. The diary and letters were carefully kept and are an insight into the understanding and expectations of the men in his situation.

Prior to the war Duncan had written excerpts for the London Scottish Gazette, entitled

‘A Non-

The following is a record of Duncan’s experiences from late July 1914. The text is

almost all taken directly from his diaries, letters and unpublished book. The writing

is very much of its time, especially in terms of political correctness. However,

it is reflective of him, his sense of humour and the society of the day. It captures

Duncan’s personal consideration of the circumstances in which he found himself. It

brings colour and detail to the experiences of one man and his war-

In with his letters and diaries was a contemporary map cut from a newspaper. Presumably printed so that people at home could see a little of where their loved ones were. I have copied it and marked with red dots, some of the towns that Duncan mentions in his diaries.

_____________________________________________________________

Wednesday July 29th 1914: [London Scottish due to go to Ludgershall training camp on Salisbury Plain.]

With Advance Party to Ludgershall for Camp. Fine and hot, short march up to Perham Down, where dumped stores and “proceeded” to Tidworth to draw tents, blankets, buckets washing, hooks bill, and all the other inconsidered trifles which are so carefully counted and checked.....Start pitching a store tent, when message comes that we are not to touch any more ordnance stuff, as it may be wanted for mobilization at once. Wars, and rumours of wars.

Thursday

Mark time and mark out ground. Watch aeroplanes, and wonder whether the battalion will be down. Word given in afternoon to go ahead. Pitch tents bell, till too dark to see.

Friday

Wet. Continue to pitch tents bell, marquees, and a cunning little explorer’s tent for the Ambulance. QM who is a man of infinite resource and sagacity, commandeers floorboards, which are in piles like gigantic bannocks, and we give all the officers floors to their tents.

Sunday

All ready for the Battalion, but wars and rumours of wars continue. News comes that the Battalion has arrived at Ludgershall... Hear the pipes along the road and break out the flag, the ‘ruddy lion ramped in gold’ as the column comes in sight. They brought with them more wars and rumours of wars, including a report that the 23rd had been stopped at Reading and ordered back to town. At tea in the Sergeant’s mess the rumours increase in variety and volume and everyone that came in had a fresh story.

Samples

The Cabinet has climbed down.

The Cabinet has not climbed down.

Germany has declared war against us.

We have declared war against Germany.

We have landed troops in Belgium.

The Germans have sunk the British Navy.

We have sunk the German Navy.

Appenrodt has declared war against Lyons.

Neutrality of Lockharts declared.

The camp will go on as usual.

We shall go back to Town about Tuesday.

A quarter of an hour after lights out the bugle goes for Colour-

Tuesday

Arrive at Paddington very early, and go to sleep in the passage until the Underground Railway commences business. Arrive at HQ still very early, find that we are dismissed, so go home, prepared for anything that might eventuate.

Wednesday August 5th 1914: First day of mobilisation.

Mobilisation order by first post. Arrived at HQ to find it ‘buzzing like a bees’ byke’ [beehive]. Took up quarters in the top gallery and awaited events. Acquired an identification disc and various other articles of “bigotry and virtue”. Beating recruits off with clubs. Hope we shall be off tomorrow. Medical inspection. Impersonation of Greek statue. Fit.

Thursday

Acquired some ammunition which is very heavy. Hope we shall be off tomorrow.

Friday

Given some pay on mobilisation. Glad. Hope we shall be off tomorrow.

Saturday

Get an entrenching tool, and go for a march out. Hope we shall be off tomorrow.

Letter of August 8 1914 London

Monday

Route marches are the idea. Sort of “Knowledge of London” tour. All the days have now become alike. Sick of HQ. Hope we shall be off tomorrow.

Letter of August 10 1914 London

Sunday August 16th

Off at last, carrying about 56 lbs of kit of various sorts, through crowds of people who request us to bring them back a present from Potsdam when we return. Very hot and heavy going, along cobbly gutters. Bivouac somewhere [Canons Park], and find the canteen cart has arrived. Loud cheers. Sleep under the stars, and dream of spiders crawling down my neck. Wake and find my dream has come true. Sleep again, using my pack as a little tent for my head. Good idea; spiders sitting round with a puzzled air, hear them tapping on the roof. Think of putting up a notice saying “for Tartan spiders only”.

Monday

Move off in rear of 13th and 16th, and help wagons up a steep hill [Stanmore Hill], singing afterwards the Wagon song of 1911, “The wagons they broke down one by one,” which is not popular among the members of the transport. People are very kind, giving us fruit as we pass through, and water as we halt.

Taken to our billets, in some stables near a lunatic asylum...The cooks having taken an extra turning and gone four miles too far, we get no dinner until after 7pm. The grousing season has now commenced.

Tuesday 18th

We got to bed somehow last night, but what will happen if it rains, do not know. At present it is like trying to get a quart of men into a pint of room. Most of us slept outside and the rest bedded down “Locked in the stable with some sheep”, as the poet sings, and seemed to be very comfortable. But we are cribbed, cabined, confined and bound in, not allowed to go into any shops or speak to the inhabitants, and we have a great idea of taking up our quarters in the lunatic asylum, and could make ourselves very comfortable, for the next month or two, in the padded room.

Letter of August 23 1914 St Albans

Friday 28

To Fortune’s Farm in afternoon. Names taken for services abroad if necessary. Miserable half hour waiting to know if numbers were sufficient for us to go as a battalion. Smoking concert in evening round camp fire. Beautiful night. Fine scene. Great circle of faces round the fire, Scots firs in the background, with stems lighted redly, and dark masses of foliage against the stars. Gavin announces number sufficient. Enormous cheers. Auld Lang Syne very impressive. Bed.

Saturday

Silent and impressive night parade at Fortune’s Farm. Nothing heard except gurgling of waterbottles. CO read articles of war in the dark. Have to be read three times, just like banns. Back to bed. Have news broken gently to me that I am orderly sergeant next week. Accept fate with calmness.

Letter of August 30 1914 St Albans

At Leavesden many days and nights are spent on exercises and operations, route marching, digging ditches and mock battling. After two weeks Duncan is allowed leave to return home on weekend leave, only to receive a telegram the next morning to ‘return at once’.

Letter of September 13 1914

Monday 14th

No Swedish drill, parade to get new rifles. Inspected by General commanding third Army, who wishes us luck. Brigadier reads us letter from front describing how Germans tried to rush night outposts by impersonating Frenchmen, coming in a crown and crying “Vivant les Anglais” masking behind them a big force of Jaeger Guards with guns and howitzers who opened fire at 100 yards. But it didn’t succeed, and they left 800 dead behind them. This is the sort of game for which we have to be prepared. Moral, shoot first and enquire afterwards.

This is our last night in the auld country. Where we are going we don’t know. Anyhow it’s France.

On the morning of Tuesday 15th the London Scottish were to march to Watford and there to entrain for Southampton, the first Territorial force to leave for France.

The London Scottish crossed the channel on the Winifredian. Duncan paints a rich picture of the crossing.

Tuesday September 15th

This is the hardest ship I ever was on, though curiously enough she is the sister ship to one on which I crossed to America a few years ago, under softer circumstances. Cattle pens are cold and clammy, sleeping on iron floors and a smell reminiscent of a partly disinfected drain. Prefer to remain on deck and smoke. As we pass through the Solent and Spithead, many ships greet us with whistles, and we are continually under the beams of search lights, until they are hidden by the shoulder of the island and as we pass Sandown Bay, the lookout station morses “What ship?” from the hill above Bembridge, and on getting our answer sends “Good luck” and then shuts off. Channel very calm in spite of high winds of yesterday, with the waning moon overhead, and the British and French lights, whose beams whole round from below the horizon.

Think of Anchor Song

“It’s Ushant slams the door on us

Whirling like a windmill o’er the dirty scud to lee.”

Think of more poetry

“May there be no more moaning at the Bar

When I put out to sea."

Explore ship to find a bar to moan at, but there isn’t such a thing...Finish thinking and realise that I am feeling very dirty. Explore ship for hot water and find some. Have a shave and feel virtuous. Go up on deck again. Everyone looks very dirty in the dawn. See French coast in the distance, and a French bird comes to meet us. More French birds appear as the sun rises, they seem to be just like the ordinary seagulls, only they squeak with a slight French accent.

Get into French train, composed of cattle trucks, twenty nine men in each. Reminded of the advertisement “Am I right for Bovril?”

Ship was hard but train is harder still. It takes three hours to start, and then it goes about 5 miles per hour. And they call it “Grande Vitesse.” Can’t go to sleep, too hard. Truck is full of benches so nowhere to lie down. People at stations very good, giving us hot coffee and things.

Arrived at our destination about midday and detailed for baggage guard. Long job getting wagons off train, loading them up and getting them off. Finally start off at dusk. Raining, put on waterproof sheets. Jammed in narrow lane, one wagon sticks in mud; unload it into cabbage field and get it out. Finally reach railway shed where we are quartered. Fine place but engines whistle too much. Invent great idea for sleeping in absence of blanket. Put legs into sleeves of overcoat and button it up, kilt over shoulders. Lucky no rats about. Rat exploring up sleeve would be unpleasant. Sound sleep first time for two nights.

Much of the next few days are spent on guard duty on the railway sidings. Finding an empty van Duncan turns it into a guard room. French troop trains keep coming through all day and night, with Algerians, Turcos and Zouaves [native North African troops serving in the French Army].

Wednesday 23rd

Fine day again. Found artist had chalked London Scottish crest on side of guard room.

Very well done. Piper in ranks [ D R Parkyn], made him get his pipes, played French

troop trains through. Turned out of our guard room at night by a terrific bump from

engine. Shifted into van in other train, half full of sacks of oats. Very comfortable

sleeping place. Siding at night makes fine picture, seven or eight huge engines

standing around, blowing huge plumes of steam, lit up by the tall electric lights,

against a blue-

Thursday 24th

Wake up feeling very dirty. Explore and find an engine with nice hot drip from tap. Have wash, and am in the middle of a luxurious shave when the beastly engine moves off. Annoyed but find another and continue shave. Same things happen again. Must be a conspiracy. Finish shave in cold water. After relief go down into town and have luxurious hot bath for 95c (ninepence halfpenny).

Friday 25th

Hurrah! Got a job to vary the monotony. Sent to – oh, one mustn’t mention names,

of course. Well, anyway it’s a big city with a very high tower in the middle of it.

Mission is to fetch a couple of stragglers. Interesting rail journey, French ladies

in carriage who get on very well with my two men whom I took as escort. The kilt

is apparently a great attraction. Arrive and become the centre of a great crowd.

Embarrassing. Dive into tube, and are again surrounded “Etes vous Hindus?” says one

good lady. “Non, Madam, les ecossaise de Londres.” Lunch at the Duval. A good friend

sends us over a bottle of wine. More power to his elbow. To the Ecole Militaire to

search for our stragglers who are not there. With a French boy scout to the office

of the Military Governor, who talks volubly to numerous French brass-

Letter September 25 1914 Paris

Monday 28th

Company on duty today, have to find ten guards of various sorts. Leaves only nine

men unemployed. Sergeant Major wants a fatigue party of thirty men. Offer him nine,

rejected with scorn. QMS wants a fatigue party of twenty men. Offer him nine. He

accepts, which I consider mean. Sergeant-

October 3rd

Inoculated against enteric. Section request unanimously that I should be first victim so as to be able to tell them what it’s like. Make sarcastic remarks, but have to do it. Doctor sticks penny squirt in under skin, do not feel it. No apparent effect. Tell Section it’s all right, and they follow suit.

Later

Rest of section rotten, all right myself, except feel as if arm hit by cricket ball.

October 4th Sunday

No bad effects, except slight headache. Nothing doing, so go for long walk after church parade. Get to little “estaminet” in village about five miles off. People refuse to let me pay for my lunch. On return hear we move tomorrow morning. Hurrah! Anything for a change. Sleep in clothes so as to be ready.

October 5th

Up at four, and march off at six, pile into train, covered with marching order and blankets rolled en bandolier, tied up with bits of string. March across Paris but pipes do not play for fear of frightening the French. Get into train at other station, send boy to buy bottle of wine for the journey, said boy does not return. Language to suit. Long and devious journey. Saw many bridges blown up by French to stop German advance. Landed at dusk at Calais platform, where spent cold and comfortless night.

October 6th

Moved off at dawn in another slow train. Sent with my section to a little station to help troops unload. Billeted in goods shed, arriving late afternoon. Artist good at lettering writes “Glenworple” at side of door in gothic characters,. Make cookhouse and turn in. Roused by sixty R.A.M.C. who come and share our billet.

October 7th

Turned out at five to take platforms for unloading horses and carts off train, and

over to goods yard. R.A. come in and get their guns off smartly. Go round village

and make map of billets. Station yard full of horses and hay and straw. Getting very

dirty. Find coalyard near, with stock of large reinforced concrete drainpipes. Steal

four of them, takes two men to carry each, also some rails, and build a wonderful

incinerator, which looks like a four-

Convenient accident whereby fell against door of locked shed, containing supply of rakes and baskets, makes job easy.

Roused at midnight to help reserve park of ammunition to off load. They always put

youngest and least experienced drivers on reserve parks, so that they give us the

hardest work, as their own men are very little help. Heavy wagons on trucks have

to be eased down sloping ramps to ground. Drag-

October 8th

Owner of drainpipes comes and says they cost four shillings each. Write out requisition in bad French, which Railway Transport Officer signs, suppose Germany will pay eventually. Chef de Gare (French for Station Master) very hot and excited every time train comes in, does all the shunting himself while others look on. First Frenchman I have ever seen doing any work. All the rest have hands in pockets all the time.

Went round billets in village with owner of drain-

More trains to unload in afternoon, but a quiet night, though have not taken boots off yet. Left knife, fork and plate unattended for a minute after dinner, when I came back, found that someone had taken knife and fork. Might have taken plate too, then I shouldn’t have had to clean it.

October 9th

Orders to get ready to move. Do so. Say farewell to inhabitants. Fair lady from Paris insists on writing her name on legs of my section in indelible pencil. Decline the honour personally, but section declares their intention of never washing any more.

Off in afternoon by slow train to Etaples, which Tommy calls “Eatables” or “Eat Apples”. Found rest of Company and got mails. Put into shed for the night, but roused at a.m. and told to get up with my section. Out sleepily and pile into train, trailing blankets after us, and bringing stores and cooks gear on a truck. Said train full of Hussars who want to know how many more blooming people they are expected to have in their truck. Appease them, and smoke the pipe of peace until dawn, when push door wide enough to sit on step. Contemplate country not yet reached by Germans.

October 10th

Arrived at out destination, St. Omer, and get out. Cavalry go on. Mac, our Section

Cook, steals coal brick off engine and fries bacon by side of the rail. Await orders

and wash under engine-

October 12th

Up at 5.30 to help unload 5 inch guns. Worked hard till 8; breakfast; just beginning to unload another train when called off to Hazebrouck. Assembled section and got on the train. Cooks, who had gone to get vegetables, were left behind. Left instructions for them to come on by next train. This place has been visited by Germans, who shot the Station Master yesterday. Most of the station staff had cleared out. Took possession of their dormitories and all had either beds or mattresses which we found in choice profusion. Also hot baths – What a luxury! ”I took my bath and I wallered”. No platform here for unloading, and had to make road across set of metals. House on hill set on fire by Germans burning furiously, and guns quite close by.

October 13th

Work again unloading pontoon train. My bed taken away because a train of wounded was in. Cleared out waiting room to make a hospital. Heard that German plane had dropped bombs on the town and killed a woman and two children.

October 15th

Must record how delighted I am with my section. They have improved no end. Marching orders today, to go to Blandeques, about four miles off. Took section by road for a change, cooks to follow by first available train. Quite a change to get on one’s feet again Marched with our piper playing proudly ahead of us, to the astonishment of the natives. Good shed near station, took possession of it, and found bales of straw all ready. Christened it “Elcho Cottage” Great excitement in village “Un Taube” German aeroplane flew over. Had shot at it and missed it, my first shot in the war. Heard heavy firing at it going on from troops in neighbourhood.

Letter October 18 1914

October 17th

Find van full of stores that someone has left behind. Boxes of jam, cheese, bread, tea, sugar and biscuits. No tobacco and no rum. All the jam is plum as usual. Why is all the jam so plumsome? Any other kind is a rarity. Load stores on a truck and push it up near billet. Ordered to Arques, the next station, march section across with piper, commandeer country cart for stores. Find very draughty shed to sleep in, where the trains come in to unload.

October 19th

Indian troops disembarking all day, very busy. Hairy great Sikhs and Pathans helping to unload wagons. One cheery old bird knocking chocks from under wheel, when all his hair came down. He stopped and did it up again, with a hairpin

October 20th

Woke at early dawn, puzzled by strange bubbling sound. See strange form squatted

at foot of my bed. Hairy old bird with big grey whiskers smoking hubble-

October 23rd

Marched into St Omer and joined up with rest of company. German aeroplane shelled by aircraft gun. No luck. Mail in – lots of letters.

October 24th

Told by Skipper to pilot naval officer in charge to Head Quarters. Useful chap. Stopped

at boot makers to buy brown laces to make the rank-

Letter October 24 1914 to Burr

October 25th

Two German aeroplanes over. All French troops fired wildly. Two cyclist scouts fired revolvers. The “Taubes” were only about 3,000 feet up. Heard after that both planes had been brought down further away. Heard firing in town and found a rifle range in old moat under ramparts. Good idea to get practice. Make enquiries from French soldiers and think it possible to arrange practice. Supper at hotel, for a change, and real whiskey and soda, the first since Paris.

October 28th

Moved into some old barracks, with beautiful steep red roofs and walls that once were white. Probable date about 1700. Nice to look at, but out of date as regards sanitation. Rooms full of dirty straw which we chuck out and burn. Think how time brings its revenges. Here are the London Scottish in barracks whence, no doubt, the French marched out to fight against us at Fontenoy, Minden and Waterloo, and the rooms we sleep in have ring with curses loud and deep against “perfide Albion”.

October 29th

Got key of the rifle range and went up. One section fired five rounds each, my own was just starting to follow when comes a message “Battalion is falling in at 3 o’clock to move off. Return at once”. Divided up rest of rum ration into water bottles and fell in. Marched out a mile and found fleet of motor buses – London motor buses waiting. Piles into them, got on top for sake of air. Did not think it was going to rain, but it soon came on. Got wet. Roads here very beastly. Narrow cobbled causeway in centre, rest soft mud. Every time a wheel went off, bus skidded and nearly upset. Very dangerous. Got off top and sat on steps. Had to get down frequently to push bus back on to road again.

October 30th

Landed at Ypres at 3am and went first to the station, where no room, then to beautiful old town hall, with wonderful beamed roof. Slept for rest of night, then marched out about 2 miles and took cover in big wood, carrying our blankets. One or two shells came pretty close. Waited an hour or two in wood. Men coming down tell us it’s ”a bit ‘ot” over the hill.

Not wanted after all. Went back, leaving blankets in shed by roadside. Told to detail two men to watch them till the transport could fetch them. Back to town hall again and then on to our old friends, the motor buses. With lights out to empty village [St Eloi]. Arrived after dark. Got into cottage and found a bed. Rations issued at night. Rum very welcome. Big gun somewhere near makes devil of a noise.

On October 31 the London Scottish first came into action at Messine.

Letter after Messine

November 1 cont.

In afternoon reached village of Kemmel. [North of Messines] It had an estaminet,

or “Herberg”, at the cross roads with some beer, and a nice girl in a clean white

apron to serve it at a penny a glass. My word! How it went down. Met trooper of Carbineers

who had been with us on the trench. Wish I could remember his name. He deserves the

DCM. Merry and bright all the time, running across to the haystacks and “first-

Got into a field – only about a couple of hundred of us – half my section missing. Reflect that as we were so scattered they are just as likely to be safe as ourselves.

QM allots us to a billet in a house down the road, quite a decent place, Belgian

family much in evidence, husband sells us milk at a penny a cup. Catch sight of self

in glass, very unshaven and hollow-

Tuesday November 3rd

Woken up in morning by wheels. French artillery arriving, the famous 75’s. Long guns, very small bore about 3 inches. French gunners very useful chaps, look as efficient as any troops we’ve seen.

Letters from Generals read out to us; glad to know we have done well. By the row we can hear, stiff fight is still going on. Glad to see French troops – they are wanted.

Thursday November 5th

Anniversary of my wedding. Inspected by big bugs. Ordnance man came and tested rifles; hear we shall get new ones. Went into town, where guileless inhabitant gave me change in local notes payable three months after end of war. Refused them with spurnery. Lots of aeroplanes in park close by, and coloured lights at dusk to guide them home. Some firing in the town at an aeroplane high up, which they thought was a German, but wasn’t. A British aeroplane swooped down between the firers and the supposed enemy, to stop them. Very plucky.

Friday November 6th

Washed in moat round owner’s cottage, a regular ‘moated grange’. Must be very pretty in summer. Drill in morning, during which pigs came and ate up company bread which had been on the tail of a cart. Went to sick parade with lumbago. Got pill to take at night. Also got new entrenching tool. Would not be without it. Pill would have done me more good than it did if I hadn’t lost it.

Saturday November 7th

Got to be ready to move at a moment’s notice. Rolled blankets and took them to transport. Completed ammunition to 200 rounds, and got orders to fall in at 3. Finally moved off at 5.30 destination unknown. Notice we are going east, so that means business. Fine evening thank goodness. Evidently heading for our old friend ‘Wipers’. Guns ahead of us get louder every minute, and there is a glare in the sky. Presently halted by motor cyclist orderly with message for Colonel. Fine picture, the Colonel and Adjutant consulting map by the cyclist’s headlight, while he explains our road to them. ‘They are shelling the town’ he says, ‘and the houses are falling all about the streets. You’ll have to go round; it’s a bit unhealthy for troops just now.’ So we go on, and the glare in the sky gets brighter and brighter, seeming to be just over the next rise.

Halt in village outside town, while scouts go and make sure of road. Cross railways where see French cuirassiers on guard, their breastplates shining in the firelight. They look like a picture by Meissonier, as if they belonged to 1820, and had got into the wrong war by mistake. The only difference in the uniform is the khaki cover to the helmet.

The old green ramparts of the town are in front of us, and our road curves to the right, between long lines of tall trees, planted as usual ten metres apart, and to out left the broad moat lies, reflecting the red glow of the sky. The ramparts and the moat have saved the city from many a fierce attack, but are impotent now against the weapons of modern ‘Kultur’.

As we go on, and get to the eastward, the shells come over our heads with the roar of an express train, and plunge into the town with a dull boom, sending up great gouts of smoke and flame. Reflect that it would be awkward for us if they fell short, and hope to goodness the bowlers will keep a good length. The towers of the old cloth hall and cathedral stand up against the sky, lit by the burning buildings, and we notice someone Morsing with a lamp from the top of the cathedral. Wonder if he is a spy giving the hits to the German observers.

Can’t read it owing to intervening smoke and trees, but think it is very probably; they had not yet begun to shell the cathedral, though the cloth hall (in which were 50 bags of mail for us) had begun to cop it.

Out onto the Menin road, where we were last Friday, and up into a farm, about two miles up on the north or left side of the road. Big barn, with straw, into which we were piled. Had to climb up a 20ft ladder, and lay very uncomfortably on the straw with my section. Small chance of getting out if we are shelled. Cooks came along with tea, but have to climb over too many people in the dark to go down and get it. Went half asleep, but awakened by a rat running over my face. Recognise this as the limit and get out. Rations left at gate by roadside, issued at dawn, but bread rather soggy, the sacks having been put in a puddle.

Move into dug-

Hear afterwards his name is Archibold. He does not hit them, but he annoys us because we are afraid they will start looking for him with shells which may hit us.

Taken out of the wood in early afternoon, into field, very open. See lots of shrapnel bursting over woods just ahead of us. Get under hedges as aeroplanes are about, then back to our wood again. Glad.

Move off again towards dusk and go on up Menin road. At Hooge find the two men (Scaife

and Gellatly) we had left with the blankets weeks ago, looking very fat and fit.

Tell them to come along with us. Off into track at right, very muddy, to dug-

It gets a bit shrappy just about now, and three or four come sprinkling about the wood; we hear the bits crashing through the trees all about, so think it wise to keep doggo for a bit.

Go to sleep until an idiot puts his foot through the roof of my dug-

We went on past ‘dug-

We turn off out of the mud into a wood on the right, and after stumbling about for some time, apparently making a crackling and trampling loud enough to wake the seven sleepers, we come to a dim line of earth heaps that turn out to be our trench.

Sussex Sergeant, who is glad to see us, say they’ve hardly fired a shot for five days, but have lost four men by snipers. Hear firing on right and left of us, but cannot see anything in out immediate front. However, someone starts blazing away, and excited private next to me fires wildly at the sky and shouts ‘They’re up in the trees.’ Considering that the said trees are tall larches with very thin stems, point out to him that his theory is unlikely, and ask him to consider what sort of idiot he is. Can hear no answering shots and no bullets are coming over. Try to stop firing, which eventually quietens down.

Three men in my bit of trench, subaltern in next bit to left, colour-

Find that the KOSBs are on our left, just across a road on which we have to have a picket at night. They pass us the word to ‘stand to’ just before dawn, as that is a likely time for an attack. When daylight comes, I find an eligible Mauser, and 200 rounds of ammunition. It is a good rifle, so decide to use it instead of my own. There is a good barbed wire entanglement in front of us, so feel fairly safe. Wood is thick, trees about four or five feet apart, field of view to daylight through stems about 200 yards, but only down two or three alleys.

Train Mauser and own rifle on two of these, tell off men in watches, and sit down and go to sleep, until wakened up for my turn to watch. No alarms during day, but pretty shelly. Find that we have shot away a lot of the wire in our flurry of the night, so one or two men get out and mend it. Saw one or two Germans during my watch, crossing to our right at far end of wood; had pot shots at them through the trees, but doubt if any of them were any the worse.

Fixed bayonets at dusk, which seems to come awfully soon. Have been asleep most of the day, during which Colonel and Adjutant came along to see how we were getting on. Did not wake me up. Beginning to get mixed up as to the days of the week.

The KOSB’s are no end good men. They have helped us a lot. Always passing the word to us when anything was going on, giving us the tip when to fire and in what direction as we could see very little, and gathering us through our first experience of trench work like the good’uns they are.

Party detailed to get rations; have tremendous adventures getting down to the supply

wagon and back. Idiots carrying tea-

Just before dawn comes a message from the KOSB’s on our left to stand to. We do so accordingly. Hear considerable firing going on but nothing happens. Gloom dispelled by dawn and distribution of rum. Very welcome. Frustrated in attempt to get share of rum belonging to man who is professedly a teetotaller, owing to his falling away from grace. My temperance lecture has no effect – he ‘tak’s aff his dram like any auld sinner.’

Wednesday November 11th

Visited by black and white kitten, who refuses bully beef with dainty scorn, jumps contemptuously across our trench and disappears in the direction of the enemy. Perhaps it’s a spy. You never know what tricks these fellows will be up to.

A bit snipy as well as shrappy today. Shots come from right. Build up traverse to stop them. Am reminded of the Jabberwocky:

‘Twas shellig and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gymble in the wabe.’

(Suggest ‘Wabe’ might be German for trench)

and the shells

‘came whiffling through the tulgy wood

And burbled as they came.’

The wood got tulgier than ever at dark, and a tremendous storm of rain and wind came

on, and in about five minutes we were wet through. Some of us had no overcoats and

I had no waterproof-

It was a wonderful night. Storms of wind, rain, thunder, guns, rifles, all going on at once. The thunder made the guns seem a very poor imitation, though sometimes it’s hard to tell t’other from which. Behind us the sky lit up by the flames of burning Ypres, into which, every now and then, an ‘express train’ sailed over our heads with a screech.

Most of us were able by this time, to distinguish our own shells from those of the enemy, and some genius invented a rhyme:

‘If the bang before the whiz

Then it’s one of ours – good biz!

If the whiz before the bang

Then it is an Allemang.’

The wind got up considerably during the storm, and the trees which were most of them scarred and splintered with shrapnel, began to fall down all over the place. It was like the transformation scene in a pantomime. Luckily the parapet of the trench prevented them from falling on our heads, but they fell all over the place and broke down our barbed wire entanglements, and when it came to morning we could not see two yards in front of ue for tree tops.

The rain had made us very cold, so to restore circulation we started digging a dug-

Tried to clean rifle, which had got into a horrible mess, also bayonet. My Mouser also got a bit jammy, luckily had small tin of Vaseline in pocket, so was able to get the action to work, though unwillingly. Grit and mud get everywhere – into ammunition pouches and all over the place. A sock over the bolt is no good as the grit gets in through the knitting. The best thing is a bandolier split up and oiled. It just buttons over nicely. N.B. the German bandoliers are much better than ours; no hard buttons to undo, the clips are sewn on so you have only to pull a thread and one comes out.

Tremendous row going on on our right today, but can see nothing from where we are, French battery gets busy a long way back, and shells burst directly over our trenches, a bit to the right of us. KOSBs kindly send a message back to stop it. Hear afterwards that we have lost several good men on our right, and that the gun team have suffered severely.

Friday, November 13th

A quiet night without much incident, except several false alarms and a good deal of sniping. In morning heard noise in underbrush ahead and got ready. Suddenly huge German jumped up, not more than twenty yards away, and turned and ran. He apparently didn’t locate us until close up. Beautiful target, impossible to miss. Colours puts his head round the traverse and says’ ‘What the devil do you mean by it? You’ve bagged my bird!’

Relieved at midnight by the West Kents. Took spade with me for walking stick. Very stiff and cramped after standing so long. Struggled out of wood and along road, or what was meant for a road, in reality a quagmire. Mud nowhere less than a foot deep, frequently three.

This is the place where a chap, who had lost his bonnet found a Black Watch bonnet, apparently lying in the mud, and on picking it up, found a head under it, which cursed him.

He therefore replaced the bonnet and remarked the mud was very deep. ‘Aye’ said the Black Watch man, ‘It is that. Am settin’ on the tap o’ an ammunition cairt.’ (The censor has no objection to the publication of this story, but does not guarantee its accuracy.)

Wandered about for what seemed an interminable time, looking for the rest of the battalion.

Saturday November 14th.

Finally got down to Zillebeck and to the railway crossing on the Hooge road, where

found the cooks (bless ‘em) with hot tea. Then up to our old friend Hooge again to

‘Dug-

Only available dug-

Called out in afternoon, took a long time to get everyone together – all three parts asleep when they did turn out. Not wanted after all, turned in again. This wood is tulgier than the trench wood; several people hit by snipers and shrapnel.

Rations came along at night, and were brought to me, being easiest to find (because of umbrella) to issue. Did so with intervals due to shrapnel, but no casualties luckily.

Tea cold, as cookers couldn’t get near. Warmed it up with rum, not bad. Dug-

It came down in the night and the other inmates kicked and struggled, half buried. Woke me up with language most improper.

Sunday November 15th

Slept most of the day, put head out once or twice to see what was going on. Too many things flying about to go visiting. More rations issued tonight, and cooks told to bring their travelling kitchen up to the wood. They make a valiant attempt and upset it in a ditch.

Monday November 16th

Turned out early hours of morning, much cheered by news that we are going into billets.

Collect everyone, after some time (two people cannot be found, having strayed off

to some uncharted island, or rather dug-

Mud worse than ever, lose my shoe in it. Down the road, down the road, down the road again, until we reach the railway. Follow it round, reaching the station at Ypres about daylight. Rails twisted all over the place, great holes in the permanent way, building smashed and burnt, and general hay made of the whole show. They were trying to get the armoured train, which had been doing them alot of harm. But they never succeeded. Good luck to it.

Halted near railway a mile or two on, and saw armoured train going up to do a bit of fancy shooting. Cheered it lustily.

Eventually arrived at the village of Westouter, very wet and tired. Billeted in house where old man is a cobbler and wife keeps shop. He had five rabbits, which we bought at a franc each, and madame made us a stew for twenty, with bacon and onions. My word it was good. Bought some wine, and what with that, and a tot of rum to wind up with, we had a topping dinner, though I didn’t have a plate to eat it off.

Commandeered a mattress and slept the sleep of the just for ten solid hours

Tuesday November 17th

Woke, wondering where I was. Saw square patch overhead and heard snore. Recognised it as that of Colours. Remembered that I was actually in a house, and that the square patch was the skylight of our attic. In spite of rabbit stew, had slept soundly without dreaming. Went downstairs, stepping over carpet of men on every bit of floor; found Madam up, with stove alight and plenty of hot water. Stole half a bucketful and took it out into yard. Had glorious wash, clean socks (much needed), and got Monsieur the cobbler to put new straps on my spats. Have a busy ten minutes trying to get some of the mud out of the insides of my shoes. Moderate success. (Mem—Spats no good for real mud; boots and puttees much better). A cold morning with white frost, invigorating, especially after wash. Displayed too much zeal to please Section, who looked with disfavour on my efforts to rouse them.

Breakfast consists of bread and bully beef. Remember that I bought a bag of raisins

yesterday, but was too tired to eat them. Raisins were all we could get in the village,

except soda -

Started off about 9am on a long and muddy march over nubbly, cobbly roads.

Still very stiff, but glad to be going to have a rest. Faces look very haggard, but probably a wash, and especially a shave , will make a great difference.

Passed a fine big gun cocking its nose over hedge in farmyard by the road-

Don’t suppose our step was any better than theirs. Mine wasn’t anyhow. Shoes are no good for this job, foot kept turning over on these cobbles. Would have been all right if spats had been tight and firm, but mine curled up like a pair of arum lilies bitten by the frost.

Tried our best to buck up as we went through Bailleule, and did manage to swing through the town with some sort of step. Saw some of HAC who said they’d been in reserve trenches, and some ‘Artists’ chafing at having done nothing yet.

Getting very baked, helping myself along with a spade. Makes a good walking stick. Have an idea we are carrying far too much – have 200 rounds of ammunition, which weigh a lot. All right going up, but now we are coming down for a rest shall not need it. Notice other troops aren’t such idiots. Fed up. Blister on left heal. Rheumatism in right arm, lumbago in small of back. Wish I hadn’t come.

Finally, after an interminable pilgrimage, arrive at a farm some place or other. Don’t know what it’s called and don’t care. Company billeted in barn. Have to climb up ladder to get onto straw. Physically incapable of such gymnastics. Put kit and rifle in corner behind door, and get someone to chuck me down a couple of trusses. Indignant entry of Madame the farmer’s wife, who cut off their tails with the carving knife – oh no – that’s the wrong story – she says the straw isn’t thrashed and mustn’t be moved. Put it back like good boys and go and forage for more. Beastly cold, but the transport have got the blankets, even two per man. Draught down back of my neck through crack of door. Steal a newspaper which it’s too dark to read and stuff it up. Too tired to bother about food, take boots off and go to sleep.

Wednesday November 18th

Woke about 5am feeling beastly cold. Put shoes on and went outside to have a pipe. Freezing hard, fields all white just like a Christmas card. Stepped on what I thought was a bit of hard ground, but found it was only a crust over about a foot of mud. Not pleased. Saw a fire a bit down the road, so went to investigate Found it was our cooks who were up early and getting the dixies going for tea. Sat by fire and got partially warm.

After breakfast took Corporal [Lockerbie] and explored in search of a wash. Found

little estaminet – L’Estaminet de la Lune-

Eau de vie indescribable, but probably potato spirit of some sort. Not very potent, and not enough of it to do any harm, anyhow, even in the morning. Met several old friends in Guards whom we found here, numbers very sadly reduced, waiting for fresh drafts. Hear that there is one coming out to us. Went and looked at village church and found RAMC quartered therein; afraid that the church is used as a hospital is no protection against German shells. Met old friend who was in army pageant of 1910 at Fulham, and asked him what episode we were doing now. We’ve all got beards like they had in the Crimea or the retreat form Corunna, but his is better than mine. Jealous. No candles to be got at any price. Means going to bed as soon as it’s dark, because there is nothing to do and nowhere to sit. Should be very glad also of a clean shirt. Afraid to think how long present one has been on, but thankful to say that up to now I am it’s only inhabitant.

Just thinking of turning in when a big motor came across the field to our billet, with bright headlamps lighting up our palatial abode. It ‘scooshed’ through the mud regardless, and when it stopped, out came our chaplain with a grand stock of cigarettes, tobacco, and pipes, which he distributed generously, not disdained to fortify himself against the night air with such hospitality as we could offer, to the extent of a tot of rum.

Thursday November 19th

Hear that we are moving today to new billets, in order to make room for drafts coming in to the rest of the brigade. Glad to say that it is only to the next village, about a mile and a half. Do not feel equal to a long march, especially when lumbago catches me bending. It’s an awful job to bend when you are straight, and worse to get straight when you are bent. However, it misses fire sometimes.

Still cling to my faithful spade; would not be without it on any account. When not in use to dig, it makes an excellent walking stick. Arrive at our billet, a prosperous farm house with the inevitable pigs, and a new bake house at the back, which we take possession of at once. Just room (with alot of squeezing) to get half the company into it, and the other half into the farm kitchen.

Plenty of straw in loft over cows, reached by rather precarious ladder consisting

of cross pieces nailed across an upright on the wall. Other half company in barn

on other side of farm-

His daughters seem to run the show, and they find us good customers for milk, and

for the ‘water bewitched’ that is glorified by the name of beer, which they buy by

the cask and retail to us in old wine bottles at two-

Letter of November 18 1914 Eric A Wright

Letter of November 19 1914

Friday November 20th

Cleaned rifles and tried to look as respectable as possible, but boots are hopeless – too much mud about to be able to keep them any way clean, the only thing is to have a good substratum of dubbin and let the mud accumulate on top of it until it is thick enough to drop off of its own accord. Mail arrives with all the letters and parcels which have been accumulating while we were in the trenches. Kind friends sent me splendid pair of boots, which, alas, prove to be just a wee bit too tight. Suppose my feet have swelled up a bit. Am torn with doubt, as to whether I try to wear them. Boots are better than shoes, less chance of losing them in the mud. But a tight boot on top of lumbago and rheumatism would be the limit. But they fit a good man, our stretcher bearer, so give them to him with my blessing.

Very cold today, snow and frost still about. Walked over to our old lady at Estaminet de la Lune with Corporal, and had another backyard wash. Might have got one at farm early in morning, but was not up soon enough. Besides, it was too cold; in other words, I funked it. Corporal, [Lockerbie] lucky man, bought beautiful Mauser pistol off a Tommy who had collected it form an officer of Uhlans [Polish light cavalry] who had no further use for same. He paid the Tommy 7 Francs 50 for it – about six shillings and threepence. Refused my offer od ten Francs for it with scorn. It is some consolation to reflect that he has no ammunition for it, and will probably have some difficulty in getting any. Confound this lumbago, shall have to see doctor in morning if not better.

Saturday November 21st

Could not sleep at all; as soon as got comfortable position, got shelled out of it by lumbago. Also mice running about seemed to be trampling like elephants. Very cold towards morning, began to doze about 6am and was woken up by horrible row underneath. M. le Maire and his family milking the cows and shouting at each other in Flemish, sounded as if they were calling each other the most awful names. Probably were doing so. Went down and got some milk, and, curiously, happened to see the rum jar among the rations. Occurred to me that a little rum might avoid any danger of the microbes from the milk. Tried it, with the aid of one of the company cooks, who suggested that I had been too modest with the rum. Added a little more, and we made several experiments until we got it right. Seems quite a good idea – propose to make a daily practice of it. Went down to sick parade to see if Doctor could give me anything for the lumbago. He gave me a tabloid and told me to keep warm and dry. Easier said than done, though most of the mud is now frozen up.. Parcel arrived from an aunt, containing a flask full of good brandy, ‘for use in a great emergency’ and a splendid khaki shirt, which I hailed with joy. Took off old shirt, which hopped away down the loft, waving its arms like a windmill.

Captured it and tied it in a bundle to be washed, but it must have come undone in the night, because when I looked for it in the morning it was gone. Parcel also contained candle lantern (folding) with three sides, all broken in transit. Filled them with oiled paper – great success.

Sunday November 22

Beastly cold again, rotten night. Church parade, service in local church, funny mixture, a Church of England service conducted by a Presbyterian Minister in a Roman Catholic Church. Sat over fire in bakehouse most of the day, feeling like a bit of chewed string. Wish I hadn’t come.

Monday November 23

Went to sick parade, took me nearly half an hour to get half a mile. Certified unfit for duty. Went back and sat over fire again. Got hump. Doubt if anything is worthwhile, somehow. Parcel from home with baccy pouch and handkerchiefs.

Tuesday November 24

Crawled down to sick parade and ordered by doctor to go to hospital. Went and packed up things, and reported to RAMC who told me to come back at 2 o’clock. Met Corporal [Hulls] being escorted back from Company parade with a sprained ankle, acquired through excess of zeal in doubling in extended order, presumably for exercise, across a ploughed field that was frozen as hard as bricks. His escort informs me that his language was horrible. String of ambulances that once were London taxies take us down to Hazebrouck, where there is a clearing hospital. Hope to get a chance of a hot bath there, would do me good. Taken to a not very clean room in a school, where bedded on stretcher in draught, and did not get very much sleep. Got hospital orderly, who had been with us at Villeneuve, to get me a suit of pyjamas from somewhere.

Tuesday November 25

All hopes of hot baths rudely dashed to the ground. No washing accommodation whatever, and the only water supply, a pump in the back yard, was broken. Had to go across the road to another hospital to get a wash at another pump, where some genius had improvised a trough. Presume that washing is not taught in French schools.

Doctor asks if I can touch my toes. Doubt it, not having been able to for twenty years. Make a valiant attempt, unsuccessful as ever, and fail dismally in getting up again. Have to do so sideways. Laughed at when I enquire if there is any chance of a hot bath.

Funny little Artillery driver in same room with us, makes us laugh by telling ludicrous storing in a slow and impressive voice. ‘Yus’, he says, ‘when I was in an elephant battery in India, we ‘ad an animal race once, and I ‘ad to train down to seven stone six to ride the elephant. ’E was the fav’rite too, and there was a lot of ‘em ‘ad their money on ‘im, and we should ‘ave won all right, we came in a easy fust, only I got disqualified on account of gettin’ lost in ‘is ear.’

At this time a rumour has been started at home that Duncan is missing. His wife hears this and begins to contact army colleagues and HQ to determine the truth.

Letters of:

November 25 1914 Eric A Wright

November 25 1914 France (Hospital)

Thursday November 26

Getting a bit better, but am fed up with this place. Might as well be back in our

billet again with the Company. Several of our men moved up into my room from downstairs;

played solo and lost sevenpence. Several people went out to-

Saturday November 28

Doctor takes my hint about rejoining, and so, with two others of ‘Ours’ [Haigh and McDonald] we are officially cured. We go out into the town to get a square meal at a place of which we have heard, called the ‘Chapeau Rouge’.

It turns out to be a sort of estaminet with a large dining room at the back, and

a long table at which a curiously assorted crowd is dining. They are French Officers,

English cavalry non-

They give us a most excellent dinner of soup, stewed kidneys, and chicken to follow, for a franc and a half. We indulge in a bottle of Vin Blanc, which goes down very well, and then the inevitable café cognac. Feel very much better, and do not think that things are so bad after all. Commandeer a motor which is going our way, and ‘scoosh’ the four miles back to our village.

Great surprise of everyone to see me. All thought I had been sent back to England.

Found that all sorts of things had been happening in my absence – the Battalion organised into double companies; hitherto we had been acting on the old system. Humourist says I am spittoon sergeant, and suggest that I should write out a requisition for some sawdust for the spittoon. Realise than he means Platoon. Slowly and surely we are coming back to things as they were a hundred years ago. Wonder if they will give us muzzle loaders and arm the sergeants with pikes.

The new draft arrived to-

Sunday November 29

Messed about getting men of draft into sections. Try to please everybody, but everybody

wants to be put in some other Section or Platoon or Company, so success is only partial.

Cold church parade in field, got leave to go to Hazebrouck after it with another

Sergeant [Sparks] Not for warmth, but to take letters to our fellows in hospital

there. Motor transport gave us a lift. Hear there is more leave going. Wonder if

I shall have any luck. Tried to buy a spoon, but could not remember French for it;

however, succeeded at last. Met Colour-

Arrived at our quarters, when other Sergeant [Sparks] was loudly congratulated on being one of the two lucky ones to get leave. Another man who will get a bath. Must really try conclusions with that pig tub. Give up all hope of getting leave now.

Letter of November 29 1914 France

Monday November 30

Left as acting Colour-

Letter of November 30 1914 France

Tuesday December 1

Cold worse. Went for route march again, this time behind the Company. Shoes, getting worn, hurt considerably. Very miserable. Gradually dropped behind and came in a long time later than the rest. First time ever done such a thing. Rotten. Determined to try and get a pair of boots, so go down to Quarter Master and succeed beyond my wildest dreams. Get good roomy boots and also a pair of puttees. Also get local shoemaker to but some big nails in the boots. Go to bed early and get good Samaritan to bring me hot rum when turned in. Very thankful. A lot of nonsense has been talked by people who want to stop the issue of rum to the troops. Those people should be taken out and stood in half frozen mud for a fortnight on end, without the chance of getting their feet really dry.

Wednesday December 2

We are in waiting. That is we are the Brigade whose turn it is to be ready to move at a moment’s notice if we are wanted. Blankets rolled at 7am, parade at 8 o’clock, ready to move off.

Then another parade ordered by the Subaltern to see if we could turn out smartly, then another by the Captain of the Double Company at the church half a mile off, and finally a Battalion alarm to see how long it took us to get us all together. Told that if we were turned out again, it would be because we were really wanted. Hoped we wouldn’t be, but we’ve got to sleep in our boots tonight as we do not expire until 8am tomorrow.

Confound it, we are turned out again after all. Told to take spades and entrenching

tools to clean up the road for the King, who is very likely coming along tomorrow.

Suppose this republic has to be made respectable for a monarch to patronise it, though

these roads are the limit. Scrape off the top foot of the mud as well as we can,

but do not see very much difference when we have finished. The middle bit is alright,

because it is paved, but the sides are hopeless. Meet old member who has come out

with the draft, who sings ribald chorus appropriate to the occasion, which is taken

up with great delight. Everybody seems in better spirits than we were a fortnight

ago, and the rest is doing us good. We are officially ‘resting’ jjust now, though

to-

Thursday December 3

Cleaned up as well as we could and turned out without overcoats, to line the road

while the King comes along. Of course, it came on to rain hard and we were all pretty

wet, but still cheerful. Told to present arms, of course when he came, and then order

arms, seize the rifle in the left hand, wave the bonnet with the right and cheer

with the other. Told the platoon I didn’t care which hand they cheered with, but

if they didn’t make more row than anybody else I’d have them court-

Cheered as loud as I could, but the King, who walked past amid a crowd of brass hats,

did not recognise me. Thought he would have remembered the handsome chap that was

by the third lamp-

Friday December 4

Return of lumbago owing to being so wet. Took matters into my own hands; did not

turn out to afternoon parade but commandeered pig-

Saturday December 5

Messing about trying to evolve platoon drill out if our inner conciousnesses. Nobody

had any drill books and nobody knew much about it. Gradually getting equipment completed.

Many gifts arriving, socks and handkerchiefs, tobacco and cigarettes. Made common

stock on mantelpiece in the bakehouse of smokables, as everyone had enough to go

on with. Got a beautiful knitted brown sweater meant for someone who had gone home

ill. All parcels for people who have been wounded or have gone home are opened, ad

the contents distributed. No good keeping eatable for people whom it is impossible

to find. Found large tin, presumable containing a plum pudding. Usual way to boil

it and open it afterwards. Did so and found it was current cake. Ingenious expereimenter

pours some rum over it and turns it into a trifle. A maist extraordinary success.

Impromptu smoker in evening, around the fire in the bakehouse. M. le Maire and all

his family, and the farm hands come in, and all laugh when we laugh, though they

don’t understand a word of the songs. Cannot get any of them to sing, even under

the influence of a mighty brew of rum punch. M. le Maire, however, makes us a great

speech, in which he says that the Ecossais are tres instruit, tres correct; promises

us five kilometres of sausages if we are there at Christmas, and says he will pleuré

great larmes when we depart, and winds up by kissing the Company Quarter-

Then he goes and makes the same speech in the kitchen, where the rest of us are sitting, and we hear afterwards that he went off to a neighbouring farm where another Company were quartered, and made the same speech to them, who though he was mad and very nearly had him arrested by the guard. But he isn’t a bad old boy though he takes guid care of the bawbees. He has two sons in the French Army; from one, he says, he hears regularly, but the other writes no more – ‘Non, il n’écrit plus....’

Sunday December 6

Find nice round cake tin that makes a good washing basin, and hide it in the outhouse for private use. Have a splendid shave, out of doors, nice sunny morning. See aeroplane overhead, very high up, going west, looks like a German. [A Taube] A few minutes afterwards hear two loud bangs, followed by a tremendous rattle of musketry. Aeroplane reappears, going towards German lines, with two of ours in pursuit. Watch them until they are almost out of sight, and see little cloud balls away down in the eastern sky, where Germans are shrapnelling out pursuit planes.

Went to church parade in the field. Having no drums, the reading desk was made of

a case of bully beef on the top of two cases that looked interesting. ‘That’s rum’,

said the Sergeant-

Monday December 7

Am Orderly sergeant. Immediately delegate as much as possible to the Orderly Corporal, whose job is no sinecure. He has to parade the sick, get the rations, pos the letters, get the mail, see lights out, milk the cows, clean the boots, do a bit of gardening, and, if it’s clay soil, make some bricks in his spare time. Go down to staff billet – very comfortable, in a real cottage with real beds – and get the orders at 6pm. Very dark, lots of mud to fall into, generously splashed by motor cyclist who is going for all he is worth through the village. Take copy to Captain, and communicate gist of the orders to the other half of our double Company, who are billeted in a cottage close by.

Find long Sergeant and short Sergeant in a cosy little kitchen, with real chairs to sit on and all. Give them the orders and wade back to billet, avoiding the fate of the ambulance man who fell into a not over fragrant pond by the wayside in the dark, and had to be thoroughly disinfected. Heard that the bombs yesterday killed one or two inoffensive civilians but did no damage.

Tuesday December 8

Our turn to be in waiting. Blankets rolled at 7 o’clock, breakfast over by 8, ready to move at a moment’s notice. Subalterns have to come round at seven to all the billets to see everything is OK. Hope they like getting up early. Ours is very gruff this morning. Wonder if he had a late night. Wonder how I shall carry all my belongings if we have to move all of a sudden. Things keep coming in anticipation of Christmas. Have wonderful collection of mufflers and socks and Balaclava helmets. Cannot find anyone to give them to. Must at all events carry my red pot. It goes on my haversack. It goes on my haversack, and is getting quite a sort of ‘pot pourri’ scent from all the different things I have had out of it. Can’t clean it, because my hand wont go into it, but the mingled reminiscences of stew and rum and tea are quite appetising. Shall see if a sauce cannot be evolved on those lines one of these days.

Wednesday December 9

Brigade order that units are forbidden to send home accounts of their doings for publication in local papers or Regimental chronicles. Believe military definition of ‘unit’ to be any number of troops exceeding one, according to D’Ordel’s tactics, so have a clear conscience. Besides, am not sending this home, but am keeping it safe against my manly buzzim. It may stop a bullet. Am a firm believer in hanging as many things as possible about oneself, when going under fire. Have seen several cases where a tin of salmon or a steam roller has stopped a bullet which ‘might have been attended with serious consequences.’

In the evening am suddenly called on to furnish a picket of twnty men, to parade at the church at once. It is the new men’s turn for duty, so go and turn out with the draft, who are in the next farm to us, telling them to get ready immediately. Time them, and find that their notion of ‘immediately’ and mine do not coincide. It is true that most of them had gone to bed at the absurd hour of 7.45 but they ought to be able to turn out in less than half an hour.

Hear that the Orderly Sergeant is mildly sarcastic when they eventually reach the church.

Thursday December 10

New cookers arrive, one for each double Company. A fine contraption with a limber, and a big chimney. One of the draft saw ours and asked what it was, and quite believed when he was told it was an aircraft gun. Did some extended order drill across a marshy field, and went in over my boots. Not pleased. Went to bed early.

Friday December 11

Woken early by a most horrible smell. Found M. le Maire and all his family pumping out some ancient cesspool under the cowshed. Wonder if I shall be ill.

Went to see football match in afternoon being no parade. Took stretcher in case of casualties. Too cold to stop long, walked home and sat over fire. Not nearly fit yet, still wish I hadn’t come.

Saturday December 12

Much warmer to-

We intend to have a ‘brew’ tonight, so arrange with one going into H... to bring back at all costs lump sugar, spices, lemons and Curacoa.

Lecture by CO at mid-

Emissary having returned from H.., set about making the punch. Tell off a fatigue party to rub sugar on the lemons so as to extract the juice from the peel, and evolve a magnificent punch, equal only to Mr Micawber’s celebrated brew. Everybody pronounces it a maist extraordinary success, and M. le Maire, who is always to the fore on any festive occasion, is in great form. Sing a song, to the tune of the ‘Laird of Cockpen’, which we tell him is a ‘chanson d’honneur’ translating it (by no means literally) between verses for the benefit of himsel’ and his admiring family.

The Mayor o’ Strazeele, he’s guid and he’s great;

His mind is ta’en up wi’ affairs o’ the state;

And when he comes out in his tricolor scarf,

He’s a regular ‘knut, à la Française -

‘Ah! Bob! Bon!’ says M. le Maire , ‘Je suis tres affairé. I messieurs, am the representation of La Republique in Strazeele, just as in all France M. Poincaré.’

Cheers for M. le Maire, who takes an appreciative drink of the punch, which, he says, is ‘trop fort’ for the family, and another verse:

The Mayor of Strazeele has owsen and swine;

He sells wi’oot licence his beer and his wine;

And oot o’ the Scottish he does himsel’ weel,

The canny auld, crafty auld Mayor o’ Strazeele.

C’est a dire, M. le Maire, that you are always very generous aux pauvres. You give all you can and you help those who have suffered in the war. M. le Maire is very pleased with this and says that it is perfectly true. We drink his health again, and proceed to another verse:

The Mayor of Strazeele ane Saturday nicht,

He drank ration rum and got fearsomely ticht;

He kissed Jimmy Paxton and made us a speech,

And promised us five miles o’ sausages each.

Told him this meant that he had not retreated when the Germans came, but he stood firm for the honour of France, He was immensely pleased at this, and told us at great length how he had been held up at the point of the bayonet for twelve hours, as surety for the good behaviour of the place.

Punch all gone by this time, so to bed, narrowly escaping serious accident on ladder, which broke triumphantly under me, in spite of Asticot’s mending. Must have been extra weight of punch.

Sunday December 13

Official period of rest is now finished; have to be ready to move at any moment. Church parade in full kit with rifles. Christmas puddings arrived in great quantities, also parcel from home containing candles among other things. Candles very rare in this desolate land, and M. le Maire very skimpy with oil for lamps. Expert made noble sauce for the Christmas pudding. Ate too much and slept all afternoon. Rumour that we move at 9 o’clock tonight. Do not believe it.

Monday December 14

Woke up and found we had not moved. Wonder how to carry all my belongings if we do move. Order comes that we have two hour’s notice, so that we can take off our boots with safety. Packed kit, but have too much for comfort. Problem is what to discard. Resolve to sacrifice knitting in favour of tobacco. In evening, some sergeant suggests game of Auction Bridge. [With Hillier, Feng and Turner] Win noble sum of fourpence.

Tuesday December 15

Wet and windy morning, spent in practising making charcoal. Light little fires all over the field and build weird erections of empty tins and sticks. Find not much use trying on small scale – combined efforts do not produce much result. Still, one keeps on learning. Intercompany football match in the afternoon, crowd on onlookers getting cold indulge in a little ‘scrum’ of their own, to keep warm. Rumour that the whole of our Division. Hope it is true, but doubt it. Our Company wins match.

Wednesday December 16

Rumour that we are to be sent to Egypt in January. Other rumour that we move at 9pm tonight. Point out that if we are to move, it will probably be at dusk, and not at a time when four hours of darkness would be wasted. Very wet route march in afternoon, good for my rheumatism and lumbago, whch keeps on making tentative attacks. Rumour that we shall be here over Christmas. Probably originated by Officers ordering turkeys to be kept for them ‘in case’. Another rumour that we shall be moving at 9 o’clock tonight.

Thursday December 19

Wake up and find that we still have not moved. Route march in afternoon – supposed to be only away for an hour, in case we have to move.

Somebody takes a wrong turn somewhere, and we find ourselves at 4pm about five miles from our billets. Fed up, wish I hadn’t come. Rumour about moving at 9pm still going strong.

Friday December 18

Very wet morning, tried experiments in platoon drill in intervals of sheltering under shed when rain became too fierce. Christmas parcels form kind friends coming in thick. Shall have awful indigestion if we move at 9pm tonight, because of having to eat what can’t be found room for outside.

Football match (very splashy) between Sergeants and Officers. Rumour that the Kaiser has committed suicide, and that we move at 9pm tonight. Huge cake arrives for Company sent by wife of one of our members. It is about 3 feet across. Everybody in horrible state of repletion. Do not know what will happen if we move at 9pm tonight.

Saturday December 19

Did not move at 9pm last night. Captain announces on parade that we need not be ready to move at two hour’s notice any more, though we are still in reserve. Very wet afternoon, no parade, played Auction instead, and won 3 Francs 50. Made some punch after dinner, and M. le Maire took the Sergeant into his parlour and gave us some coffee, and, as someone remarked, ‘the best potato spirit I have ever tasted.’ Company Quarter Master Sergeant afraid to join us, for fear of being kissed again. Rumour that we shall certainly not move before Christmas. Glad, getting to quite like this place, except for the mud. Hope the rumour is true.

Sunday December 20

No church parade today, owing to absence of padre. Told at 9am that we are in waiting

for twenty-

Scouts appear on the ground, wonderfully dresses in straw costumes with black faces,

like the King of Borria-

Message comes that we are to be ready to move at 5pm Get down to our battalion rendezvous at the Church, and move off to the minute, getting a last glimpse of M. le Maire standing at the corner, actually pleuring great larmes.

We are the second regiment in the Brigade, in order of march. Do not know in the least where se are going, whether it’s trenches of base for home. Several people seem to think it’s home, but it doesn’t look like it. Evidently something is up. Down a hill to a railway station, where a train is waiting headed for the west. Rumour comes down that we are going down to Havre in it. Almost begin to believe it, especially when we check at the level crossing, but in a minute we move on across the line, and everyone laughs and the rumourists are chaffed about it.

Wonder where we are off to. We are heading south-

The night seems interminable. One sings, occasionally, and our three pipers play us along; three only remain of the nine that came out, but several of us are beginning to feel it a bit, and the pack becomes heavier every minute. At one halt, man sitting on edge of deep farm drain, incautiously lays his rifle on the edge, and it falls in. Fish for it with sticks, but the drain has concrete sides and is about six feet deep. Perhaps one day it will be recovered, a rusty relic of the Great War.

Luckless man borrows one for the time from the Company Cook. ‘You’ll soon get a spare one in the trenches, ‘ says the cynical old hand. Somebody notices curious lights in the sky, and starts a Zeppelin scare. Presently said light reveals itself as the moon, coming from behind a cloud. She is very near her setting now, though as we are heading west at the moment, the mistake is pardonable.

Come to fair-

Begin to see signs that there is something going on. Hear rifle fire away to our

left, and see star shells in the distance. A regular firework display going on. Getting

very tired and sleepy, but persevere. Pitty the fellows who have been playing football.

Start up ‘John Brown’ but the chorus is a bit half-

Come to a village and ask a woman who is at the door of a cottage what the name of it is. She replies something that sounds like ‘Aaarj!’ Can’t make much of that, until other Sergeant asks a soldier, who is watching us go by. ‘What’s this place?’ ‘Hinges!’ answers the Tommy promptly. Thus we have both the spelling and the pronunciation. Hear that we are now only two or three miles from our billet. Good biz. This will be a twenty miler before we have done with it. Expert with map says we are making for Bethune. Reminds one of the ‘Three Musketeers’ but, personally, do not feel equal to much swashbuckling just now. Could not swash any bucklers, but could do a pint of beer nicely. No luck however.

At last we get to Bethune, well lighted up all the way by star shells away on the left, and find it full of Indian baggage trains and ammunition columns. Rumour that we have been sent for to support the Indian divisions, which have been having a tough time of it.

Monday December 21 2am

Halt for some time in the street while our billet is being found, and find a clean bit of pavement against a wall to sit on.

Go to sleep, until pulled up by two of the boys (could not have got up by myself) and bed down in gymnasium with nice soft tan floor. Make my bed between some parallel bars, and slumber peacefully from about 3am until about 8 o’clock, when Cooks, who have got into yard of some sort next door, rap on the window and shout for Mess Orderlies to fetch tea for breakfast. Foraging parties go out and return with loaves and buns from a neighbouring shop. Clean rifles and ammunition, and told to be ready at a moment’s notice.

Sit down and smoke, while quartet sings most delightfully, in parts, various songs and choruses, being encored again and again.

Get order to fall in at 11 o’clock, and move off through square or ‘place’ of the

town. Which way are we going, east or west? East it is, we’re ‘for it’ again. As

we go down the long straight road out of the town, can see the rest of the Brigade

in front of us, for we are to be in reserve, and, as optimists say, may not be wanted

at all. No use speculation, all one can do is take what comes. One realises the supreme

unimportance of tomorrow because there may never be one. Fine view to our right,

to the south and south-

Meet lot of Indian Cavalry along the road, and very fine fellows they look. Horses

in the pink of condition, and one of our aeroplanes sails close above our heads,

just as we are leaving the out-

Carry on for about seven miles, then turn off to the left. Hullo, this is beginning to get interesting. Village to the right of us, with big pyramidal heap of slack and coal mine.

See shrapnel bursting over village, but not near enough to us to do any harm.

Open out with intervals between sections, and go on for a bit. Coming to another village, of which most of the houses are smashed up. Some of them, however, are all right, at least the roofs are still on.

Halt for a bit, and get into a trench in a field to right of road, in case of shrapnel. Trench very narrow and muddy, so let the others get in first, and sit on edge of it ready to plop down if any unwelcome visitors come along. Notice horses of C.O. and Adjutant being led back, so conclude that we shall not have much farther to go. Presently are moved on again (glad I didn’t get into that narrow and dirty trench) into the village.

Distillery close by, with tall chimney, knocked about by shells. This is the place where some members of a certain regiment came off worst in an imbroglio with some raw potato spirit, inadvertently left by the Germans in the bottom of a vat.

Halted in main street of village, where met for the second time old friend who used to be Sergeant in the Liverpool Scottish, now a dispatch rider for one of the Indian divisions. He, hospitable soul, gave us some stew, which was highly appreciated. One or two bullets audible; apparently this street is in a straight line with somewhere. Good water at pump in corner of yard in front of school, very refreshing. Fill my red pot and have a good drink.

Have conscientious objections to being hit without being able to hit back, so tell the boys to keep into side of road. Tremendous storm comes on, heavy rain pours down in lumps, get out waterproof sheet and pin it over shoulders with kilt pin. Wily man discovers little cottage down in a back garden sort of place. Room enough for four or five, so tell other Sergeants and get into it. Violent attempts to light stove, only partially successful. Two Frenchmen in inner room, who clear out after a bit, making more room for us. Go out in order to see if anything is going on, and find everyone has disappeared. Find main body of Company in school opposite, and leave word with trusty man to call us if there is a move on, showing him where we are to be found. See Subalterns wandering about, looking like wet hens, having found no shelter, so invite them to our palatial abode.

Find stove going, so make some soup with Oxo cubes, very good; top off with biscuits,

peppermint bull’s-

Our road goes to the right, parallel with the enemy’s lines apparently at about 500

yards from their trenches. Scout there to show the way, Officers go on to reconnoitre.

Road very snipy. Hear that the Germans have got the range of it, and pay a good deal

of attention. They keep on throwing up blue lights. Divide up into sections and go

round the corner and down the road, flopping into wet ditch whenever blue light appears.

Get whole Company through without any casualties and get shelter behind hedge at

further end by head-

Then in single file to our left across fields, plenty of shell-

Snipers pretty busy, and every time a light-